Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the most populous countries in the South Asian region. The country is facing rapid urbanisation due to factors such as poverty, natural disaster and better employment opportunities which causes people to move to urban areas. Its capital, Dhaka, is one of the planet’s fastest growing megacities, where an estimated 300,000-400,000 migrants, mostly poor people from rural areas arrive annually. A vast majority of these migrants end up living in slums or informal urban settlements. These informal urban settlements tend to be located in low-lying, flood-prone, poorly drained areas, with limited formal rubbish disposal and minimal access to clean water and sanitation. These areas are severely crowded, with between four and five people living in houses of just over 100 square feet. These are generally excluded from public sector resources, severely limiting residents’ access to formal education, health care, water and sanitation.

The urban poor are mostly engaged in low-paid, labour-intensive work in the informal sector, with rickshaw-pulling and construction day labour being the dominant employers followed by small business. Around 80% of new migrants (males) are employed as rickshaw pullers. For women living in the informal urban settlements, employment options are limited to garments work, domestic service, and manual labour. These women tend to be excluded from jobs in the transport sector, most skilled craft work, service industry and retail sector jobs.

The predicted rise in population density will be severely exacerbated by climate change. A sea-level rise of 1.5 metres will submerge 15% of the country’s landmass, increasing the population density and the challenges in meeting people’s basic human rights. Although urbanisation drives economic development of a country, there are growing concerns of its effects on food security, health, and environment.

Health and social issues

In Bangladesh, provision of healthcare for the people living in informal urban settlements is inadequate, and falls under the responsibilities of the local government and not the Ministry of Health. Lack of coordination between government bodies, shortage of human resource and inadequate financial resources lead to poor quality of services for the urban poor.

The newly migrated urban poor are faced with a pluralistic health system, consisting of informal providers such as local traditional healers, quacks, drug shop attendants; as well as government and NGO-run health facilities. These people often do not seek formal healthcare due to issues of distance and transportation cost, long waiting lines, lack of information and neglect in last visit, which discourage them from going to these providers. Instead, they prefer the local informal providers and NGOs, which are more accessible.

Many non-profit organisations provide healthcare services in these slums, particularly maternal and child care services. These include BRAC Manoshi, Dushtha Shasthya Kendra’s health care programme, Marie Stopes maternal and reproductive health services etc. Besides these, there is also the Urban Primary Health Care Services Delivery Project, a public private partnership with local NGOs to help provide primary healthcare services to slum dwellers in some areas.

People living in these areas experience social, economic and political exclusion. Evidence shows large disparities among the urban population between ‘slum’ and ‘non-slum’ areas in terms of food security, nutrition, access to clean water and sanitation, and health indicators. Air, noise and water pollution lead to direct health hazards. There is a lack of ventilation and outdoor space. Eviction and the threat of eviction have severe social, economic and psychological effects, all of which reinforce poverty and social exclusion and its impact on the lives of the urban poor.

Governance

The rights of people living in informal urban settlements in Bangladesh are neither recognised nor protected. There is no explicit or comprehensive policy on urbanisation and urban poverty. This constitutes a major constraint for NGOs, donor agencies, and even some government officials working in informal urban settlements. The state’s ambivalence towards urban policy is shown in the conflicting dual metropolitan power structure. Although the Dhaka City Corporation is autonomous and its mayor and ward commissioners are elected by Dhaka’s citizens, its power is controlled by the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Co-operatives. Implicit in the lack of urban policy is the assumption that informal settlements are temporary, resulting in the denial of programmes explicitly for the urban poor.

As informal settlements are considered ‘illegal’, populations who live there often have no official address and are commonly denied basic rights and entitlements, including the right to access water, sanitation, health services and education. Informal urban settlements continue to be demolished by successive governments. Eviction and the threat of eviction, as well as the absence of a policy framework, discourage interventions to improve residents’ long-term prospects.

Often in these slum settlements, a partisan based system is found. It is seen that business protection, arrangement of livelihood, provision of amenities in households such as water or electricity are given out as favor, and in exchange the slum dwellers have to show loyalty to the local powerful individual in the form of votes, or participation in rallies for a specific political party.

Government neglect has created a space in which non-state institutions compete to govern access to and use of resources, such as land for housing, services, jobs and urban space, in more or less benign or criminal ways. State actors are often complicit in this competition. Water and sanitation facilities are governed by diverse actors from the public, private and NGO sector, leading to sharp contrasts in wellbeing across sites.

Non-governmental actors are critical to efforts to provide services and improve the conditions of people living in informal settlements. The organised participation of female and male settlement dwellers in planning and controlling services has been found to be vital for their success. However, monitoring and regulation of NGO services are weak and accountability mechanisms to the people they serve are unclear. Organisations of informal settlement dwellers are essential to improve conditions and reduce exclusion. Projects have shown that people who live in informal settlements are willing and able to organise and pay for services if the opportunity is given. The Coalition for the Urban Poor is an association of organisations working to improve the lives of people living in informal settlements.

Read more

Sabina Faiz Rashid, Strategies to Reduce Exclusion among Populations Living in Urban Slum Settlements in Bangladesh. J HEALTH POPUL NUTR 2009 Aug;27(4):574-586.

Bangladesh Health Watch report 2014, Urban Health Scenario, looking beyond 2015, (Eds Ahmed SH, Islam FK, Bhuyia A)

te Lintelo D.J.H., Gupte J, McGregor J.A., Lakshmana R, Jahan F. Wellbeing and urban governance: Who fails, survives or thrives in informal settlements in Bangladeshi cities? Cities 72 (2018) 391–402.

Banks, Nicola, Urban Poverty in Bangladesh: Causes, Consequences and Coping Strategies (October 25, 2012). University of Manchester, BWPI Working Paper 178. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2166863 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2166863

Sajedul Islam Khan & Md Nazirul Islam Sarker* & Nazmul Huda & A. B. M. Nurullah & Md Rafiuz Zaman, 2018. “Assessment of New Urban Poverty of Vulnerable Urban Dwellers in the Context of Sub-Urbanization in Bangladesh,” The Journal of Social Sciences Research, Academic Research Publishing Group, vol. 4(10), pages 184-193, 10-2018

Institute of Governance Studies, BRAC University. (2012). State of Cities: Urban Governance in Dhaka. Retrieved from http://dspace.bracu.ac.bd/xmlui/handle/10361/2055

Posts on Bangladesh

Living during the pandemic in urban informal settlements in Bangladesh

This photo-narrative book was developed with community members from Green Land (Khulna), Bajekazla (Rajshahi) and Shyampur (Dhaka) communities, as part of the ARISE Responsive Fund in Bangladesh. It tells the stories of how many marginalised people in urban informal settlements of Bangladesh were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they came together to respond […]

Perceptions of and Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccination among Urban Slum Dwellers in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Abstract Vaccine hesitancy or low uptake was identified as a major threat to global health by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019. Vaccine hesitancy is context-specific and varies across time, place, and socioeconomic groups. In this study, we aimed to understand the perceptions of and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination through time among urban slum […]

The effects of social determinants on children’s health outcomes in Bangladesh slums through an intersectionality lens: An application of multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA)

Abstract Empirical evidence suggests that the health outcomes of children living in slums are poorer than those living in non-slums and other urban areas. Improving health especially among children under five years old (U5y) living in slums, requires a better understanding of the social determinants of health (SDoH) that drive their health outcomes. Therefore, we […]

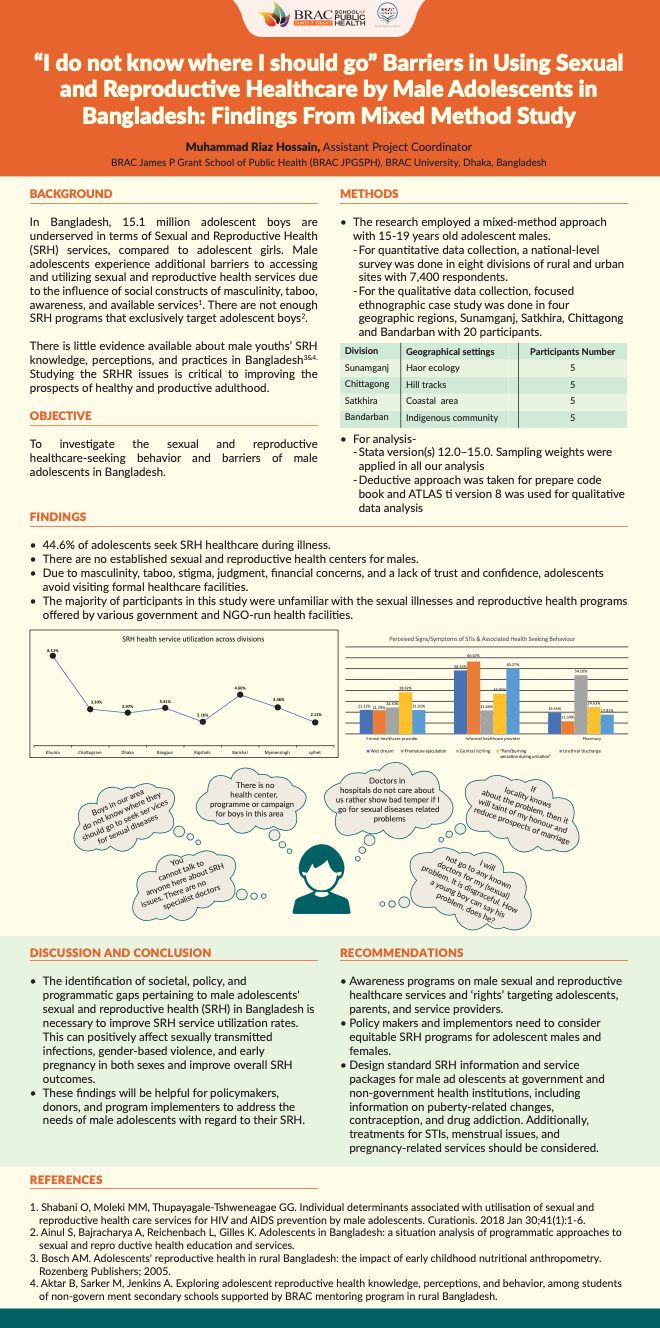

“I do not know where I should go” – Barriers in using sexual and reproductive healthcare by male adolescents in Bangladesh: Findings from a mixed method study

“I do not know where I should go” Barriers in Using Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare by Male Adolescents in Bangladesh: Findings From Mixed Method Study This poster by Muhammad Riaz Hossain was presented at the National Adolescent Health Conference in Bangladesh. It was funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands project titled ‘Understanding Sexual […]